Clinical practice is stressful. The negative effects of stress and burnout can be harmful and expensive for the individual and their organisation. It affects patient safety, sickness absence, staff turnover, and organisational culture. However, staff can learn to cope with stress more effectively, if they have the right tools and information.

Working Stress is a unique evidence-based app and ‘serious’ board game that teach clinicians how to cope with stress and avoid its negative effects.

Working Stress is a collaborative effort between academics, psychologists, clinicians, therapists and a leading ‘serious’ games developer. The core development team is:

In the 2016 NHS Staff Survey found 37% of staff reported feeling unwell due to work-related stress, and the cost of sickness absence alone has been estimated at £2.4 billion a year. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that occupational health issues:

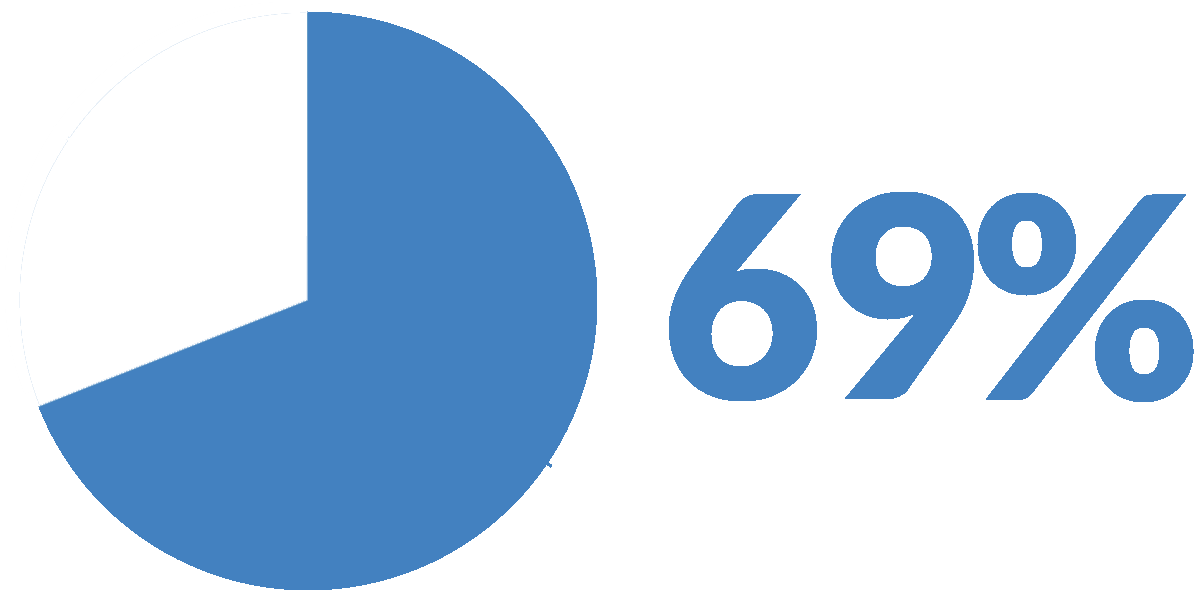

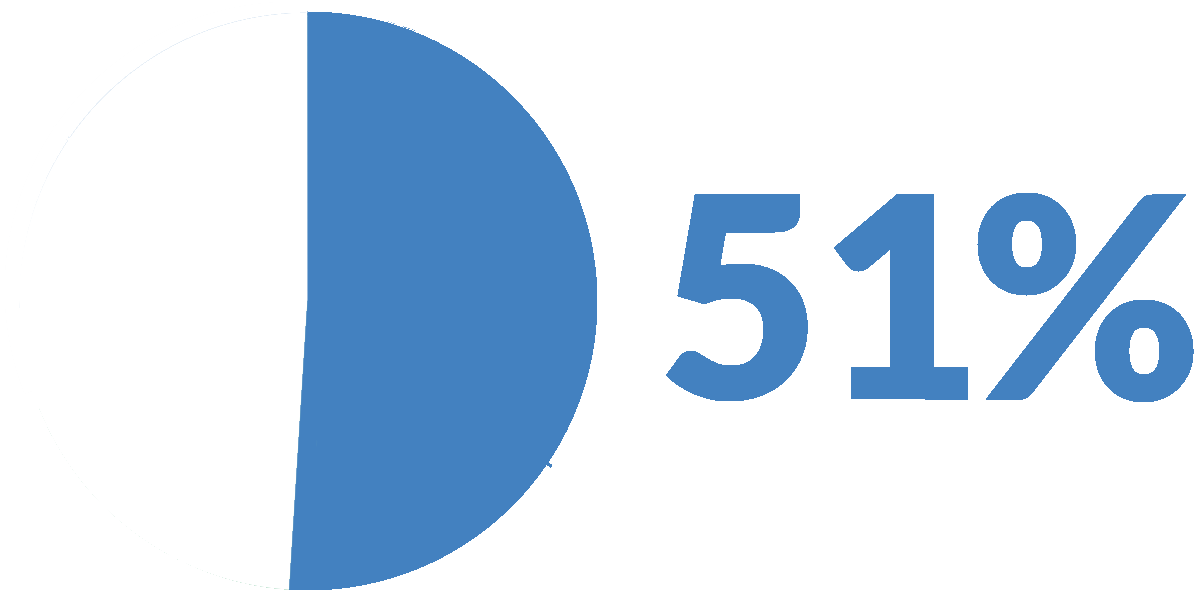

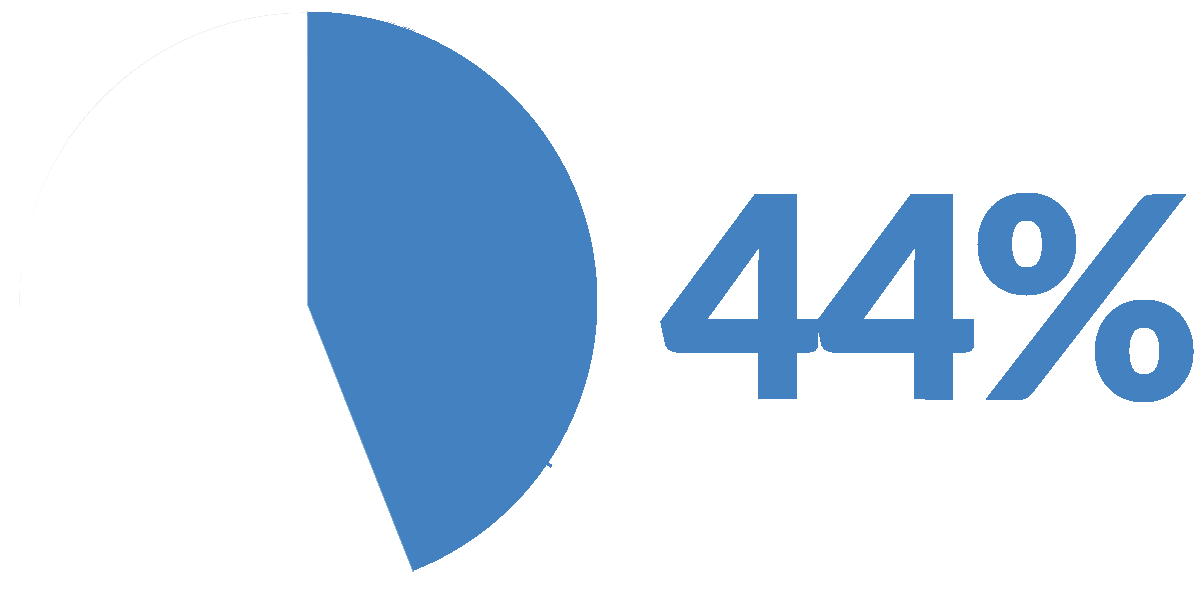

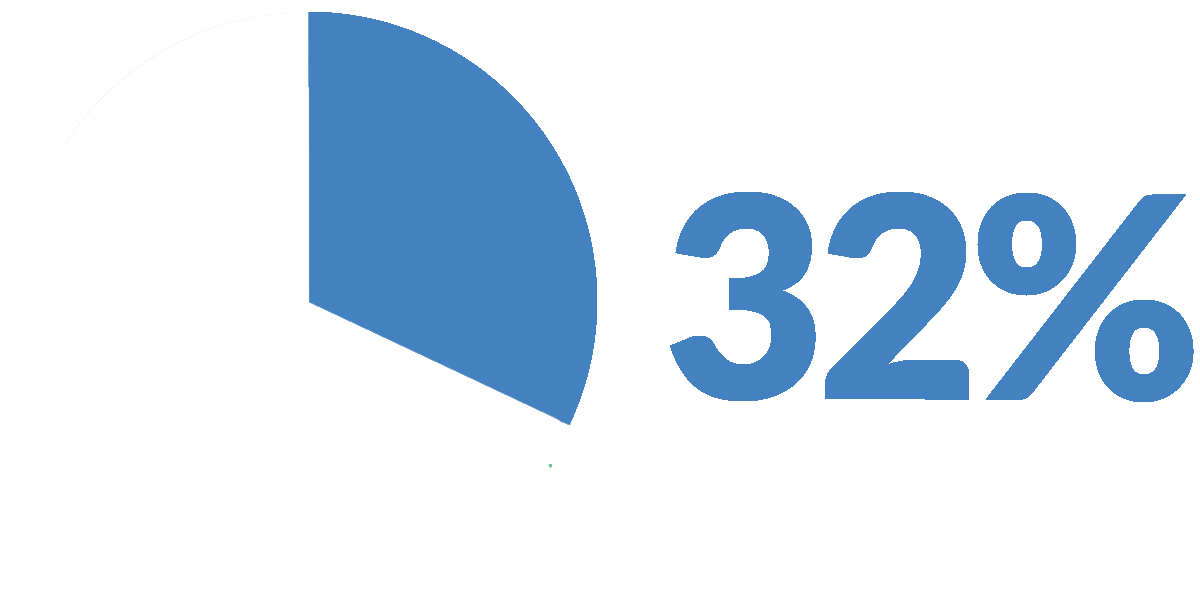

Dr Caroline Kamau and Asta Medisauskaite, creators of Working Stress, assessed occupational distress among doctors in their 2017 study ‘Prevalence of oncologists in distress: Systematic review and meta‐analysis’¹(Journal, 2017). Their analysis showed:

Stressed at work

Experience depression

Sleep problems

High levels of burnout

Psychiatric morbidity

They concluded that“Occupational distress reduces career satisfaction, affects patient care, and increases the chances of…switching to another area of medicine; therefore, future research should explore appropriate interventions.” In response to their own conclusions Kamau & Medisauskaite designed Working Stress, 3 simple online interventions to help reduce levels of occupational distress and burnout. Working Stress teaches clinicians how to view and cope with stress in a more positive way.

Working Stress is based on widely recognised academic research and cognitive frameworks. The Transactional Stress Model (Lazarus 1990) proposes that an individual’s response to stress is based on two appraisals. The first establishes how stressful, threatening and controllable they expect a situation to be. The second reviews the resources they feel are available to cope with the situation. The combination of these appraisals and coping strategies act as mediators between stress and its effect on the individual and their ability to deal with the stress.

The way that individuals appraise stress and how they deal with it dictates the response and outcomes they experience. Some will experience negative responses and outcomes, others will not.

Working Stress targets an individual’s cognitive appraisal of stressors and improves their ability to cope with them. It does this by providing specific information about work-related stress, grief and burnout and the impact they can have psychologically and physically. It then presents a range of evidence-based coping strategies that clinicians can apply in daily working life.

Working Stress enables clinicians to view work-related stressors more positively and cope with them more effectively. This results in better psychological, physical and organisational outcomes (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987).

The Working Stress interventions were tested in a Randomised Control Trial (RCT) ‘Occupational Distress in Doctors: The Effect of an Induction Programme’ in 2017. The 227 participating doctors were all based in the UK and came from a range of specialities and seniority:

Analysis of the results demonstrated significant changes among participating doctors. In the trial Working Stress reduced the number of doctors suffering from:

It also reduced levels of fatigue and improved doctors’ perceptions of their employer and working conditions. Doctors also increased their use of positive coping strategies, such as using humour, seeking emotional support and self-reflective practice. Doctors who took part in the pilot study said:

A pre-publication summary of the RCT results is available, please contact us at info@focusgames.com or call +44 (0)141 554 5476.

1Medisauskaite A, Kamau C. Prevalence of oncologists in distress: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4382